Experiential Perceptions

Classifications, definitions, explanations with respect to both classic/typical and Advanced Free Will framework usage.

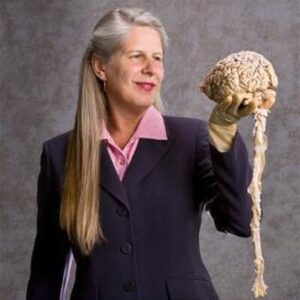

The Harvard scientist who had a stroke and gained profound insights is Jill Bolte Taylor. A neuroanatomist, she suffered a massive hemorrhagic stroke in 1996 at age 37, which affected the left hemisphere of her brain.

During the stroke, she observed her brain functions—motion, speech, and self-awareness—shut down, offering her a unique perspective as both a scientist and a patient.

Her experience led to heightened awareness of the brain’s right hemisphere, which she describes as fostering peace, connection, and a sense of unity with the universe.

Taylor documented her journey in her 2006 book, My Stroke of Insight: A Brain Scientist’s Personal Journey, and her 2008 TED Talk, which went viral, further amplified her message about brain function, recovery, and living with greater mindfulness.

She views the stroke as a transformative event that reshaped her understanding of consciousness and human potential.

BEINGON Research :: EP Overview

Classifications and descriptions of EPs -experiential perceptions-: including, but not limited to, senses, feelings, emotions, and cognition awareness.

summary

Experiential perception refers to the comprehensive array of ways in which humans experience and interpret sensory stimuli, emotions, and cognitive awareness. It encompasses processes such as sensory perception, which involves the registration and interpretation of data through the five senses—sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell—as well as emotional and cognitive experiences that shape personal and social interactions. Notably, the brain processes an overwhelming amount of sensory information yet can consciously engage with only a fraction, illustrating the intricate nature of perception and its essential role in human cognition and behavior. [1] [2]

The significance of experiential perception lies in its impact on individual self-concept, emotional regulation, and interpersonal dynamics. Research demonstrates that one’s self-perception, influenced by emotions and cognitive biases, can significantly affect mental health outcomes, such as anxiety and self-esteem. [3]

Furthermore, understanding how cultural contexts shape perception adds another layer of complexity, as differences in background can lead to varying interpretations of sensory stimuli and emotional cues. [4] [5]

Theoretical frameworks such as Gestalt psychology, which emphasizes holistic processing, and David Marr’s model of visual information interpretation have advanced our comprehension of experiential perception. These frameworks highlight the dynamic interplay between physiological processes and psychological experiences, underscoring the importance of qualia—subjective qualities of experiences—in shaping consciousness and self-awareness. [6] [7] [8]

Debates surrounding experiential perception often focus on the nature of qualia and the limitations of physicalist approaches in explaining conscious experience. The Knowledge Argument, exemplified by Frank Jackson’s thought experiment involving Mary the color scientist, challenges the completeness of physicalist explanations by suggesting that experiential knowledge cannot be fully encapsulated by scientific descriptions. [9] [10] [11]

This ongoing discourse underscores the philosophical complexities inherent in understanding the relationship between subjective experiences and objective reality, making experiential perception a critical topic in psychology, philosophy, and neuroscience.

Overview

Experiential perception encompasses a broad range of human experiences, including sensory perceptions, emotions, and cognitive awareness. It plays a crucial role in how individuals interact with and interpret their environment. The process of perception begins with sensory stimulation, where the brain receives approximately 11 million bits of information every second, yet consciously processes only about 40 bits at a time [1].

This highlights the complexity of perceptual processes and the intricate relationship between neuroscience and sensory processing.

Types of Experiential Perceptions

Sensory Perception

Sensory perception involves the registration and interpretation of stimuli through the five senses: sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell. This continuous process transforms sensory input into organized experiences that allow individuals to make sense of the world around them. Perception is defined as the process of one’s ultimate experience of the world, involving stages of stimulation, organization, interpretation, evaluation, memory, and recall [2].

Emotional and Cognitive Experiences

Emotions are integral to experiential perception, influencing individuals’ behaviors and self-perceptions. A positive self-perception can lead to increased confidence and optimism, whereas a negative perception may result in low self-esteem and anxiety [3].

Additionally, cognitive awareness shapes how experiences are processed, where factors such as personal biases and cultural expectations play significant roles in social perception [3].

Theoretical Frameworks

The understanding of perception has evolved over time, influenced by various theoretical frameworks. Gestalt psychology, for example, emphasizes the holistic nature of perception, suggesting that the whole experience is greater than the sum of its parts [6].

David Marr’s model bridges the gap between neural mechanisms and psychological phenomena, providing insights into how the brain interprets visual information through both bottom-up and top-down processes [7].

The Role of Qualia

Qualia, the subjective qualities of experiences, are fundamental to understanding consciousness and self-awareness. Without qualia, individuals would lack the inner experiences that give meaning and purpose to their existence, reducing human behavior to mechanical responses [8].

This highlights the importance of subjective experience in the broader context of perception, illustrating the profound impact it has on human life and interaction.

Classifications of Experiential Perceptions

Experiential perceptions can be classified into various types based on the sensory modalities involved and the nature of the perceived stimuli. Understanding these classifications helps in comprehending how individuals interpret and respond to their environment.

Types of Perception

Visual Perception

Visual perception involves the ability to interpret and utilize visual data, including colors, patterns, shapes, light, distance, and movement. This type of perception is critical for navigating the environment and understanding visual stimuli that are essential for survival [12].

Auditory Perception

Auditory perception pertains to the interpretation, understanding, and utilization of sounds, words, and other auditory stimuli. It encompasses recognizing pitch, tone, volume, rhythm, and melody, which are vital for communication and environmental awareness [12].

Tactile Perception

This type of perception is related to the sense of touch and includes detecting texture, temperature, pressure, and pain sensations. Tactile perception plays an important role in physical interactions with objects and understanding one’s surroundings [12].

Gustatory Perception

Gustatory perception refers to an individual’s ability to detect various tastes, such as salty, bitter, sweet, sour, and umami. This type of perception is crucial for evaluating food and its chemical composition, thereby influencing dietary choices [12].

Olfactory Perception

Olfactory perception involves interpreting and comprehending different smells. The ability to recognize and distinguish between various odors is essential for survival, particularly in identifying food safety and environmental dangers [12].

Emotional Perception

Emotional perception allows individuals to perceive and interpret the emotions of others through facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice. This aspect of perception is crucial for social interactions and understanding interpersonal dynamics [12].

Social and Person Perception

Social perception refers to the ability to interpret and react to socially significant cues, while person perception goes beyond this to involve constructing and maintaining impressions of others. These processes are vital for navigating social environments and forming relationships [13].

Depth Perception

Depth perception enables individuals to perceive spatial orientation, including distance, height, and depth, which is essential for coordinating movement and accurately reaching or throwing objects [13].

Influences on Perception

Perceptions are influenced by a myriad of factors, including beliefs, values, prejudices, expectations, and life experiences. Cultural context also significantly shapes perception, as demonstrated in studies showing differences in visual illusions between Western and non-Western cultures [4] [5].

Additionally, perceptual hypotheses, informed by personal experiences and expectations, play a critical role in how sensory information is interpreted [4].

Descriptions of Experiential Perceptions

Experiential perceptions encompass a wide range of sensory modalities and cognitive processes that inform our understanding of the environment and ourselves. This section explores the various dimensions of experiential perception, including sensory input, self-perception, and the impact of emotions and cognition.

Sensory Modalities

Sensory modalities are the different channels through which we perceive sensory information. The primary modalities include vision, audition (hearing), tactile sensation (touch), olfaction (smell), and gustation (taste) [14] [15].

Each modality responds to specific types of stimuli, allowing us to interpret our surroundings uniquely. For instance, seeing a bright light engages the visual modality, while the scent of freshly baked bread activates the olfactory modality [16].

In total, sensory modalities can number as many as 17, including submodalities such as pressure, vibration, and temperature within the general sense of touch [17] [18].

Selection and Organization of Perception

The process of perception begins with selection, where our brains prioritize which stimuli to attend to, often unconsciously [19].

This selection process is crucial due to the overwhelming amount of sensory input we encounter daily. Once stimuli are selected, they are organized into coherent perceptions, enabling us to interact meaningfully with our environment [19].

Sensory processing involves integrating inputs from multiple modalities to create a cohesive understanding of our surroundings [14].

Self-Perception

Self-perception is another critical aspect of experiential perception, shaped by personal experiences, cultural contexts, and social feedback [3].

An individual’s perception of themselves can significantly influence their behaviors, emotions, and overall well-being. For example, positive self-perception may foster confidence and optimism, while negative self-perception can lead to low self-esteem and anxiety [3].

This perception can change over time and across different life domains, highlighting its dynamic nature [3].

Emotional and Cognitive Influences

Experiential perceptions are also affected by emotions and cognitive processes. The relationship between cognition and emotions is complex; while some theorists argue that emotions are prewired responses, others suggest that cognitive processes play a significant role in shaping emotional experiences [20].

Affective self-awareness and experiential feelings may provide greater benefits than a purely cognitive focus [20].

Additionally, beliefs, values, and expectations can significantly shape how we perceive stimuli and experiences [5].

Cultural factors can also lead to variances in perception; for instance, people from different cultural backgrounds may experience visual illusions differently [5].

Theoretical Perspectives

The Knowledge Argument

The Knowledge Argument, formulated by Frank Jackson in 1982, posits that there are certain aspects of consciousness and qualitative experience that cannot be fully understood through physicalist explanations alone. This argument has generated extensive philosophical debate, drawing attention to two main strategies that echo Jackson’s initial proposal. The first, identified by Daniel Stoljar and Yujin Nagasawa, involves the knowledge intuition, which asserts that no amount of physical information can provide a complete understanding of the qualitative nature of experiences, often referred to as qualia [9] [21].

The second strategy involves thought experiments akin to Jackson’s famous example of Mary, who, despite having comprehensive knowledge of color and vision, has never experienced color herself, raising questions about the completeness of physicalist accounts of knowledge [9].

Emotion Theories

Various theories attempt to explain the emotional experience, each presenting a different perspective on how emotions are formed and understood. The James-Lange Theory of Emotion, for instance, suggests that physiological reactions occur prior to and give rise to emotional experiences. According to this view, our emotions are essentially a reflection of our body’s responses to stimuli [22] [23].

In contrast, the Cannon-Bard Theory argues that emotional experiences and physiological responses occur simultaneously, challenging the sequential nature proposed by James and Lange [22].

The Schachter-Singer two-factor theory further refines these ideas by suggesting that emotions are the result of physiological arousal combined with cognitive interpretation of that arousal [22].

Critics of the James-Lange theory, such as Hutto, Robertson, and Kirchhoff, emphasize the complexity of emotions, proposing that they are not solely biological but deeply intertwined with environmental interactions [23].

This critique suggests that understanding emotions requires consideration of both internal physiological states and external stimuli, indicating that emotions cannot be fully comprehended through a purely physiological lens [23] [24].

Gestalt Psychology

Gestalt psychology, emerging in the early 20th century through the work of Max Wertheimer and his colleagues, focuses on how individuals perceive stimuli as organized patterns rather than disparate elements. The central tenet of Gestalt psychology is that the mind tends to form a cohesive whole, reflecting self-organizing tendencies in perception. This perspective introduces principles such as the laws of proximity, similarity, and closure, which describe how humans naturally group elements to create meaningful perceptions in a chaotic environment [25] [5].

The laws of grouping illustrate that our brains prefer to interpret sensory input as structured and complete rather than as isolated components, highlighting the importance of holistic processing in perception [25] [5].

This approach underscores the complexity of experiential perceptions, encompassing not just sensory information but also cognitive and emotional dimensions that influence how we understand our world.

Research and Studies

Research into experiential perceptions encompasses various disciplines, including psychology, philosophy, and neuroscience, yielding insights into how individuals perceive and interpret their environments. A significant area of study focuses on the influence of cultural contexts on perception. For instance, Segall et al. (1966) illustrated how individuals from Western cultures, who are accustomed to straight-edged architecture, exhibit different perceptual biases compared to individuals from non-Western cultures, such as the Zulu of South Africa, who are more attuned to round structures [4] [5].

This phenomenon highlights the interaction between environmental features and perceptual experience. In addition to visual perception, studies have shown that olfactory perception can also vary across cultures. Ayabe-Kanamura et al. (1998) demonstrated that individuals’ abilities to identify and evaluate odors differ significantly based on cultural backgrounds, indicating that sensory experiences are not universally perceived but are instead shaped by cultural contexts.[4]

Further research has expanded into the realm of unconscious processes and their roles in shaping attitudes and decision-making. For instance, mere exposure effects, a form of attitude formation identified by Zajonc (1968), suggest that repeated exposure to stimuli can positively influence attitudes without the necessity of conscious awareness. [4]

This effect persists even when individuals encounter stimuli subliminally, as evidenced by Kunst-Wilson and Zajonc (1980), indicating that unconscious processes can have a profound impact on preferences and perceptions. [4]

The exploration of consciousness and unconscious processes also engages philosophical discourse. Notable contributions include the works of Stoljar (2006) and Strawson (2006), who argue for complex interrelations between physicalism and experiential perceptions, including the implications for theories of mind and consciousness. [26] [27] [21]

This philosophical examination is complemented by empirical studies in neuroscience, such as the work by Creswell et al. (2013) and Custers & Aarts (2010), which link unconscious thought processes to decision-making performance and goal pursuit, respectively. [28]

These interdisciplinary studies highlight the intricate dynamics of experiential perceptions and underscore the importance of both cultural and unconscious factors in shaping human cognition and emotion.

Applications

Experiential perceptions play a critical role in various therapeutic and psychological contexts. Understanding these perceptions allows for the development of effective interventions and enhances emotional intelligence.

Therapeutic Approaches

One of the most significant applications of experiential perceptions is within cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). This widely used therapeutic approach is predicated on the interconnections among thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. By identifying and challenging negative thought patterns, individuals can modify their emotional responses and behaviors, effectively “rewiring” the emotional circuitry of the brain to create new, healthier pathways [29].

The integration of experiential techniques within cognitive therapies, such as Schema Therapy, further supports the treatment of emotion regulation problems by addressing both cognitive and experiential components of psychological distress [20].

Humanistic and Existential Approaches

Humanistic and existential theories emphasize human potential and self-actualization, centering on the individual’s experience. For instance, person-centered therapy, developed by Carl Rogers, underscores the importance of creating a nurturing environment where individuals can thrive. This approach fosters self-exploration and growth through unconditional positive regard, empathy, and genuineness in the therapeutic relationship [30].

Such therapeutic environments enhance clients’ ability to engage with their emotions and experiences meaningfully.

Emotional Intelligence

In addition to therapeutic settings, the understanding of experiential perceptions contributes significantly to the development of emotional intelligence. Recognizing and comprehending the cognitive processes underlying emotions allows individuals to better manage their feelings, leading to improved interpersonal relationships and personal well-being. Enhancing emotional intelligence can be likened to upgrading one’s emotional operating system, enabling a more nuanced understanding of one’s own and others’ emotional experiences [29].

Educational and Research Contexts

Furthermore, recent developments in problem-solving strategies and innovations in therapeutic formats indicate that a deeper understanding of experiential perceptions can inform educational programs and research initiatives. Such insights promote effective coping strategies and enhance overall mental health literacy among diverse populations [31].

By incorporating experiential awareness into educational curricula and research designs, practitioners can facilitate a more profound understanding of emotional dynamics in various contexts.

Challenges and Controversies

The study of experiential perceptions, including the various dimensions of conscious experience, raises significant philosophical challenges and controversies that continue to engage scholars. Central to these debates is the relationship between subjective experiences and objective descriptions, often encapsulated in discussions of qualia and the knowledge argument.

The Knowledge Argument

The knowledge argument posits that there are certain aspects of conscious experience that cannot be fully explained by physicalist accounts of the mind. This is exemplified in the famous thought experiment involving Mary, a color scientist who knows all the physical facts about color but has never seen it herself. Upon experiencing color for the first time, she allegedly gains new knowledge, suggesting that not all knowledge is reducible to physical facts [10] [11].

Proponents of this argument, such as Frank Jackson, argue that this indicates a fundamental limitation of physicalism, leading to ongoing debates about the nature of consciousness and its implications for the mind-body problem [9] [28].

Representationalism vs. Phenomenal Concepts

Another significant controversy lies in the debate between representationalism and the phenomenal concept strategy. Representationalists contend that conscious experiences are primarily constituted by their representational content, implying that there are no intrinsic features of experience beyond what is represented [32] [33].

This view faces criticism from those who argue that such an account cannot adequately capture the subjective quality of experience, or qualia, which are seen as essential to understanding conscious experience [21] [11].

Critics, including those who advocate for the phenomenal concept strategy, maintain that our introspective access to conscious experience reveals aspects that representationalism overlooks. This has led to further inquiries into how we understand and describe the quality of experiences, particularly in distinguishing between conscious experiences and the mental phenomena that might be perceived as interchangeable terms in the literature [28] [34].

Acquaintance and Knowledge

Additionally, the notion of acquaintance, particularly as discussed by philosophers like Balog, presents challenges to traditional epistemic views on knowledge and perception. The debate hinges on whether our direct experiences of qualia can provide a basis for knowledge that is distinct from knowledge gained through physicalist explanations [35] [21].

This ongoing discourse suggests that understanding consciousness may require an integration of various epistemological frameworks to adequately account for the complexity of experiential perceptions.

STORM Research Tool

The article is based on reserach using Stanford University’s STORM.

STORM is a specialized AI based on an LLM which automates various phases of research by streamlining the process of gathering information, while ensuring academic integrity through rigorous citation practices.

Senses:

- Sight

- Hearing

- Taste

- Smell

- Touch

Feelings:

- Happiness

- Sadness

- Anger

- Fear

- Surprise

- Disgust

Emotions:

- Love

- Joy

- Excitement

- Calm

- Anxiety

- Frustration

- Contentment

- Grief

- Euphoria

- Anticipation

Physical Sensations:

- Warmth

- Cold

- Pain

- Pleasure

- Tingling

- Numbness

- Itch

- Thirst

- Hunger

Cognitive States:

- Awareness

- Focus

- Confusion

- Curiosity

- Understanding

- Doubt

- Imagination

- Insight (Sudden clarity or realization that connects fragmented knowledge)

- Pattern Recognition (The ability to identify complex patterns or relationships across disparate fields)

- Hyperlexia (Unusually advanced reading or decoding skills often seen in savants)

- Numerical Fluency (Effortless manipulation and understanding of numbers, as seen in mathematical savants)

- Total Recall (Perfect memory for specific details, common in savant cases)

- Synesthesia (Blending of sensory experiences, where one sense triggers another, such as seeing sounds or tasting colors)

Social and Interpersonal Experiences:

- Empathy

- Connection

- Isolation

- Trust

- Conflict

- Cooperation

- Betrayal

- Support

Psychological States:

- Mindfulness

- Stress

- Relaxation

- Motivation

- Boredom

- Depression

- Enthusiasm

- Flow (A state of deep immersion and effortless concentration in a task)

- Mental Overload (Feeling overwhelmed by too much information or stimuli, common in cognitive savant experiences)

Moral and Ethical Perceptions:

- Justice

- Fairness

- Guilt

- Forgiveness

- Compassion

- Integrity

Aesthetic Experiences:

- Beauty

- Sublimity

- Awe

- Serenity

- Harmony

- Creative Vision (A deep and clear inner sense of form, composition, or innovation, often described by artists and savants)

Cognitive Specializations

1. Islets of Ability:

This term is often used in savant syndrome to describe isolated areas of exceptional skill or hyper-specialized cognitive abilities in areas such as memory, calculation, or artistic talents. These abilities appear to exist in stark contrast to the individual’s overall cognitive functioning, especially when they have developmental conditions like autism.

2. Hyperlexia:

This refers to an advanced ability to read and decode written words, often seen in some savant cases, typically in conjunction with autism. Individuals with hyperlexia can sometimes read at an extremely young age but may struggle with other aspects of cognitive or social development.

3. Prodigious Memory:

Many savants exhibit extraordinary recall abilities, particularly in specific areas such as numbers, facts, or music, but this is often described as rote memory rather than deep understanding. This form of memory recall is frequently associated with savant syndrome.

4. Hyper-Specialization:

This term is used to describe the focused nature of cognitive abilities in savant syndrome, where extraordinary skill is found in one specific domain (like mathematics or art), but there’s often limited generalization of those skills into broader cognitive areas.

5. Splinter Skills:

A term often used in the context of autism and savantism to describe narrow, highly specific abilities that stand out from the individual’s overall developmental profile.

6. Synesthesia-like Perception:

Some savants report experiencing cross-sensory perceptions (such as seeing sounds or feeling numbers), though not always in the strict sense of synesthesia. This perceptual phenomenon is sometimes observed in savants with extraordinary artistic or musical abilities.

7. Idiot-Savant (historical term):

While now considered outdated and inappropriate, “idiot-savant” was a term used historically to describe individuals who showed severe cognitive disabilities but had extraordinary abilities in specific areas. This term has evolved into the more neutral savant syndrome today.

8. Prodigious Savant:

A term used to describe individuals with savant syndrome whose abilities are so extraordinary that they would be considered exceptional even by neurotypical standards.

Miscellaneous Perceptions:

- Freedom

- Power

- Vulnerability

- Resilience

- Inspiration

- Courage

- Novelty Creation (The ability to synthesize entirely new ideas or forms from existing information)

- Hyper-Creativity (Sudden bursts of intense and innovative thought, leading to groundbreaking insights)

- Perceptual Overlap (The blending of different perception categories, such as cognitive EPs blending into sensory EPs)

from X/Twitter post

by Akiyoshi Kitaoka, an experimental psychologist who studies visual illusions as well as makes illusion artworks.

AI Podcast: !ISO framework

!Information !Subjective !Objective

Experiential Perceptions and Advanced Free Will

Our Minds Are Connected According To Math

Edward Frenkel | AfterMath

Revolutionary ideas in mathematics, quantum physics, philosophy, and Jungian psychology, as well as interconnections between these subjects. Edward explains in simple and accessible terms – based on mathematics! – that our minds are connected to each other at a much deeper level than is ordinarily understood.

What is Time? @stephen_wolfram 's Groundbreaking New Theory

— Prof. Brian Keating (@DrBrianKeating) February 14, 2025

Timestamp:

00:00 Intro

00:51 The true nature of time

24:42 The role of computational irreducibility in thermodynamics

29:52 The Ruliad and the nature of observers

53:28 The role of gravity in the computational… pic.twitter.com/LRTXeSFL9v

Timestamp:

00:00 Intro

00:51 The true nature of time

24:42 The role of computational irreducibility in thermodynamics

29:52 The Ruliad and the nature of observers

53:28 The role of gravity in the computational universe

1:06:14 Dark matter and the discreteness of space

1:12:54 Paradigm shifts in science and technology

1:20:18 Exploring the cosmic microwave background (CMB)

1:31:32 Outro

Click the image above to view in expanded size.

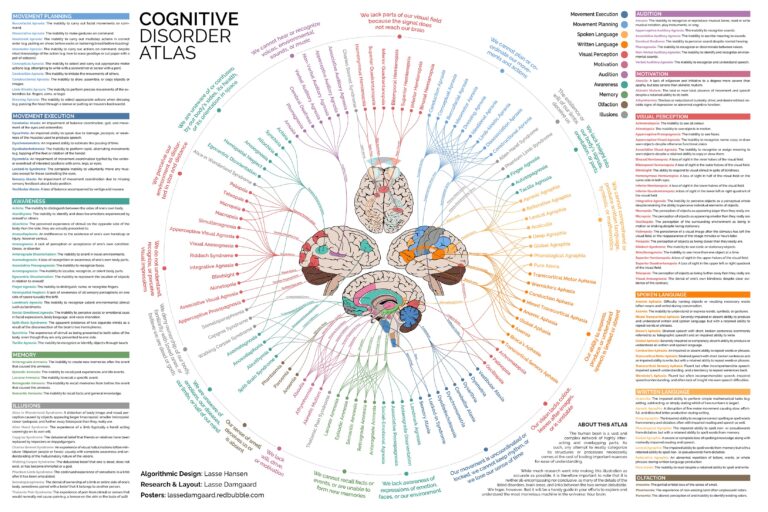

You can also browse this list and others on the Cognitive Atlas org website: https://www.cognitiveatlas.org/

The Cognitive Atlas is a collaborative knowledge building project that aims to develop a knowledge base (or ontology) that characterizes the state of current thought in cognitive science.

Mark Zuckerberg says AI models display intelligence but they don't have consciousness or will like people do:

I think one of the more interesting philosophical findings from the work in AI so far is, I think people conflate a number of factors into what makes a person a person. So there’s intelligence. There’s will. There’s consciousness. And like I think we kind of think about those three things. As if they are somehow all the same right. It’s like if you’re intelligent then you must also have a like a goal for what you’re trying to do. Or you must have some sort of consciousness.

But I think like one of the crazier sort of philosophical results from the fact that, okay you have like meta AI or chat GPT today, and it’s just kind of sitting there. And you can ask it a question and deploy like a ton of intelligence to answer a question. And then it just kind of shuts itself down. Like that’s intelligence that is just sitting there without either having a will or consciousness. And like I just think it’s not a super obvious result that that would be the case. But I think a lot of people they anthropomorphize this stuff. And when you’re thinking about kind of Science Fiction, you think that okay, you’re going to get to something that’s like super smart. It’s going to like want something or like be able to feel…

_ _ _

Full video: https://youtu.be/7k1ehaE0bdU

X:

X: